|

|

Weest Paraat DE PADVINDERIJ (SCOUTING) deel 1 |

De webmaster als welp. |

| "Een Padvinder glimlacht en fluit onder alle omstandigheden." | ||

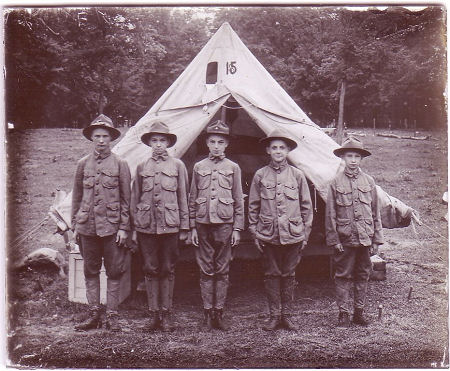

Glazen lantaarnplaat zonder omlijsting met een foto van vijf padvinders in uniform voor een tent tijdens een kamp. Zij dragen het originele uniform dat gemodelleerd was naar de Amerikaanse legeruniformen met een jas met veel zakken en de kniebroeken met daaronder leggings. (c. 1910) |

De padvindersbeweging voor jongens werd in 1908 opgericht in Engeland

door een officier van de cavalerie, Robert (later Lord)

Baden-Powell. In dat jaar had hij een boek geschreven met de titel

‘Scouting for Boys’ (Verkennen voor Jongens), waarin spellen en wedstrijden

werden beschreven die hij gebruikt had bij de training van zijn troepen. Het

boek werd erg populair onder de Engelse jongens. |

|

|

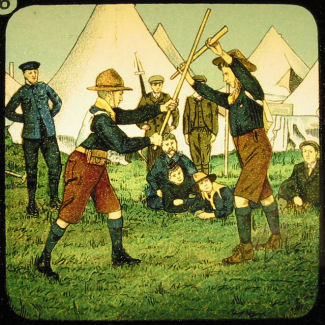

Chapter I. - IN CAMP WITH BADEN-POWELL. Originele bijgesloten tekst; niet vertaald.

|

||

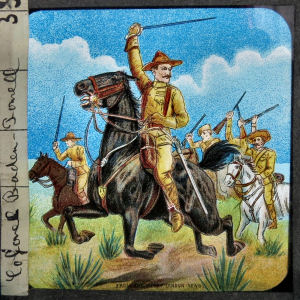

Baden-Powell's idee was dat jongens zichzelf zouden organiseren in subgroepjes van zo’n zeven jongens, de zogenaamde patrouilles, onder leiding van één van hen. Om een Padvinder te kunnen worden moest een jongen beloven de padvinderswet te gehoorzamen. Daarin stond ridderlijk gedrag en het doen van ‘elke dag een goede daad’ centraal. De symbolen van de padvinders waren onder meer het hand geven met de linkerhand, de Franse lelie en het motto ‘Weest Paraat’. Hoewel B.P. bedoeld had dat zijn ideeën alleen zouden worden gebruikt door jeugdorganisaties in Engeland, verspreidde de Padvinderij zich snel naar andere landen. Aan het einde van de 20e eeuw waren er padvindersgroepen in 110 landen. Sinds 1920 werden er om de vier jaar internationale bijeenkomsten gehouden, de ‘jamborees’. Op de eerste Jamboree in Londen ontving B.P. de titel ‘chief-scout of the world’. In 1937 werd de Jamboree voor de eerste keer in Nederland gehouden, in Vogelenzang; de tweede keer was in Dronten, in 1995. In 1910 richtte Baden-Powell in Engeland de Girl Guides (Gidsen) op, naar aanleiding van de vele verzoeken van meisjes die geïnteresseerd waren in de padvindersbeweging voor jongens. Hoewel de padvinderij aanvankelijk bedoeld was voor jongens van 11 tot 15, richtte hij een parallelorganisatie op voor jongere jongens, de ‘welpen’. Foto: Robert Baden-Powell, geportretteerd op een 8,2 x 8,2 cm fotografische lantaarnplaat.

Boeren Oorlog, Kolonel Baden-Powel, Oprichter van de Padvinderij. Lantaarnplaat 8,2 x 8,2 cm. |

2. Hoisting the Flag.

The Scouts are to be true patriots, and so the national flag is hoisted over the

camp, and, as it flutters upon the breeze, is saluted with all due honour

and

respect. But does the General want to foster the military spirit-to train an

army of juvenile soldiers? By no means. There are peace Scouts as well as

war Scouts, he says, and he believes in this free, open-air life, under

discipline and with every incentive to self-reliance and self-control as the

very best means to foster the spirit of good citizenship. Raleigh, and

Drake, and Capt. John Smith, in the days of Elizabeth; Capt. Cook and Lord

Clive; Ross and Franklin amid the Arctic snows; Speke, and Baker, and

Livingstone, cutting their way through the forests of tropical Africa: these

are the examples the General holds up for imitation - pioneers of empire,

but good citizens, good men, peace Scouts. and

respect. But does the General want to foster the military spirit-to train an

army of juvenile soldiers? By no means. There are peace Scouts as well as

war Scouts, he says, and he believes in this free, open-air life, under

discipline and with every incentive to self-reliance and self-control as the

very best means to foster the spirit of good citizenship. Raleigh, and

Drake, and Capt. John Smith, in the days of Elizabeth; Capt. Cook and Lord

Clive; Ross and Franklin amid the Arctic snows; Speke, and Baker, and

Livingstone, cutting their way through the forests of tropical Africa: these

are the examples the General holds up for imitation - pioneers of empire,

but good citizens, good men, peace Scouts. |

|

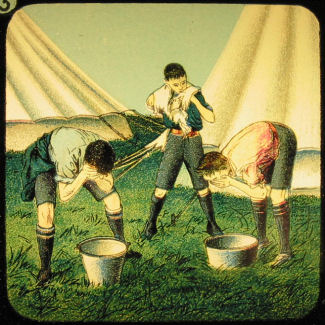

3. Morning Toilet. The morning toilet

starts the daily life of the Camp: it's a simple operation, if an important

one. A bit of soap, a towel, a bucket of water from the

spring, and there you are. If you haven't brought a tooth-brush, make one with a dry

stick, frayed out at the end. That's wrinkle No.1; it's marvellous what a

lot of things you'll learn in a Scouts' Camp! You'll learn the value of

personal cleanliness - the value of tidiness. Listen to the General: "The

Camp ground should always be kept clean and tidy, not only to keep flies

away, but also because if you go away to another place, and leave an untidy

ground behind you, it gives so much important information to enemy's Scouts.

For this reason Scouts are always tidy, whether in camp or not, as a matter

of habit. If you are not tidy at home you won't be tidy in camp; and if

you're not tidy in camp, you will be only a tenderfoot and no Scout." Isn't

that good advice?

spring, and there you are. If you haven't brought a tooth-brush, make one with a dry

stick, frayed out at the end. That's wrinkle No.1; it's marvellous what a

lot of things you'll learn in a Scouts' Camp! You'll learn the value of

personal cleanliness - the value of tidiness. Listen to the General: "The

Camp ground should always be kept clean and tidy, not only to keep flies

away, but also because if you go away to another place, and leave an untidy

ground behind you, it gives so much important information to enemy's Scouts.

For this reason Scouts are always tidy, whether in camp or not, as a matter

of habit. If you are not tidy at home you won't be tidy in camp; and if

you're not tidy in camp, you will be only a tenderfoot and no Scout." Isn't

that good advice? |

||

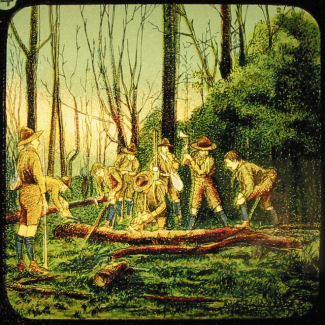

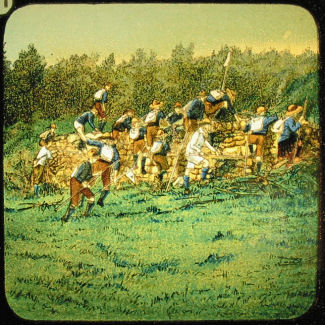

4. Cutting Wood.

We want wood for

our Camp-fire, poles for our huts or tents, or other purposes. So off we go

to the woods to cut it - of course, having obtained

permission first. Every Scout should know how to use an axe or bill-hook for chopping

down small trees and branches. You think it's very easy, and so it is, when

you know how - like a good many other things. But, "it is a matter of

practice to become a woodcutter, and you have to be very careful at first,

lest in chopping you miss the tree, and chop your own leg." There's another

wrinkle for you. And whilst you are in the woods, the General will tell you

all sorts of yarns about the Scouts, red, and white, and black, whom he has

met on the frontiers of the Empire, of men lost in the woods, and how to

find your way by noticing landmarks, and to tell in what direction the wind

is blowing by throwing up little bits of dry grass, or holding up your wet

thumb and noticing which side feels coldest. Or you may learn

something of how wild animals are tracked by their spoor, or of the trees

and plants which grow around you - for all these things belong to "Woodcraft,"

and that is one of the Scout's accomplishments.

permission first. Every Scout should know how to use an axe or bill-hook for chopping

down small trees and branches. You think it's very easy, and so it is, when

you know how - like a good many other things. But, "it is a matter of

practice to become a woodcutter, and you have to be very careful at first,

lest in chopping you miss the tree, and chop your own leg." There's another

wrinkle for you. And whilst you are in the woods, the General will tell you

all sorts of yarns about the Scouts, red, and white, and black, whom he has

met on the frontiers of the Empire, of men lost in the woods, and how to

find your way by noticing landmarks, and to tell in what direction the wind

is blowing by throwing up little bits of dry grass, or holding up your wet

thumb and noticing which side feels coldest. Or you may learn

something of how wild animals are tracked by their spoor, or of the trees

and plants which grow around you - for all these things belong to "Woodcraft,"

and that is one of the Scout's accomplishments. |

||

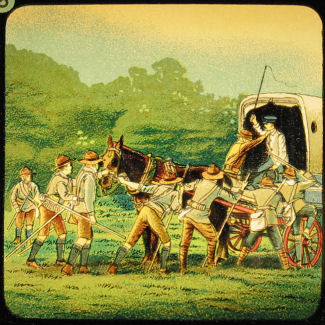

5. Provisions for the Camp. Well,

we have got our wood, and return to Camp. Hooray! here's

the provision wagon: now for dinner. We learn some of the mysteries of

Camp-cooking. "The three B's of life in Camp

are

the ability to cook bannocks, beans, and bacon." Bannocks are cakes or buns

cooked in the hot ashes of the Camp-fire-but if we want real bread, we must

have some sort of oven - an old earthenware pot or tin box, the fire piled

over it, or a clay oven more or less properly built. Or we may twist a strip

of dough round a stout club, carefully peeled and heated, and stuck into the

ground close to the fire to toast. Only we mustn't let our bread burn in

either case, and of course Scouts never do let it burn. As for our bacon, we

may fry it or boil it, and we shall certainly boil our beans and our

potatoes, if we have any, and make some tea in our tin "billy"; and what

more do you want in the way of a square meal? But these are only the

rudiments of Scout cookery: cooking meat in a coating of clay, making

"hunter's stew," or roasting "Kabobs " - these are the higher developments

of the art: we shall learn all about them in Camp with Baden-Powell. are

the ability to cook bannocks, beans, and bacon." Bannocks are cakes or buns

cooked in the hot ashes of the Camp-fire-but if we want real bread, we must

have some sort of oven - an old earthenware pot or tin box, the fire piled

over it, or a clay oven more or less properly built. Or we may twist a strip

of dough round a stout club, carefully peeled and heated, and stuck into the

ground close to the fire to toast. Only we mustn't let our bread burn in

either case, and of course Scouts never do let it burn. As for our bacon, we

may fry it or boil it, and we shall certainly boil our beans and our

potatoes, if we have any, and make some tea in our tin "billy"; and what

more do you want in the way of a square meal? But these are only the

rudiments of Scout cookery: cooking meat in a coating of clay, making

"hunter's stew," or roasting "Kabobs " - these are the higher developments

of the art: we shall learn all about them in Camp with Baden-Powell. |

||

|

|

||

|

Persoonlijke herinneringen: Toen ik een jonge jongen was, dat was in de jaren vijftig, was ik zoals zo velen van mijn vriendjes, lid van de padvinderij. Wij kwamen iedere week op zaterdagmiddag bij elkaar in ons clubhuis, een verbouwde garage, en onderwierpen ons daar aan de soms wat merkwaardige ceremoniën.  Zo moesten wij aan het begin van de bijeenkomst vanuit alle hoeken en gaten van het clubhuis naar het midden van de ruimte rennen en daar, op onze hurken in een cirkel rondom onze leider gezeten, de yell aanheffen ‘Akela, wij doen ons best, wij dob, dob, dob, dob, dob!’. Waar we de rest van de middag mee vulden weet ik niet meer. We droegen in die tijd nog een uniform, de jongeren, de ‘welpen’ hadden een groen petje op hun hoofd, de ouderen, de ‘verkenners’, een hoed met een brede rand zoals wij verder alleen maar in films zagen over de Canadese bereden politie en zo. Bij de welpen hadden de leiders vreemde namen als ‘Chiel’, Baloe en ‘Baghera’, namen die kwamen uit het Jungleboek van Kipling. We droegen een driehoekige das om onze hals; iedere groep had zijn eigen kleuren, en zowel de welpen als de verkenners droegen zomer en winter een korte broek, hoewel die bij de leiders, de hopmannen, vaak tot ver over de knieën viel. Dat stond nogal belachelijk, maar zou toch nog eens mode worden, toen ik ouder was. Ik heb echter altijd zeer beslist geweigerd mij zo’n ‘hopmanbroek’ aan te schaffen. Je werd als padvinder geacht iedere dag (tenminste) één goede daad te doen. Als voorbeeld werd gegeven een oud vrouwtje te helpen de straat over te steken. Er zullen in die tijd heel wat oude vrouwtjes die even aan de kant van de weg hebben staan treuzelen tegenstribbelend de weg over zijn 'geholpen'. |

7. A Camp Loom.

There's no end to the useful information we pick up during the daily life of

the camp. Look at this Camp-loom, for instance.

You

want a spring-mattress? All right - collect dry bracken, fern, grass,

heather, straw, and so on, and then to work. Drive a row of stakes, 2 ft. 6

in. wide firmly into the ground: opposite to them, at a distance of 6 or

7ft., plant another row, or two stakes and a crossbar, as in the picture.

Connect your two rows of stakes with stout cords, carrying the continuation

of the cords back over No.1 row for some 5ft. extra, and there fasten them

to a loose crossbar or " beam." This beam is then moved up and down at slow

intervals by one Scout, while the remainder lay bundles of bracken or straw,

&c., in layers alternately under and over the stretched strings, which are

thus bound in by the rising and falling of the beam. With this loom you can

also make grass or straw mats, with which to form tents or shelters, walls

or even carpets. You

want a spring-mattress? All right - collect dry bracken, fern, grass,

heather, straw, and so on, and then to work. Drive a row of stakes, 2 ft. 6

in. wide firmly into the ground: opposite to them, at a distance of 6 or

7ft., plant another row, or two stakes and a crossbar, as in the picture.

Connect your two rows of stakes with stout cords, carrying the continuation

of the cords back over No.1 row for some 5ft. extra, and there fasten them

to a loose crossbar or " beam." This beam is then moved up and down at slow

intervals by one Scout, while the remainder lay bundles of bracken or straw,

&c., in layers alternately under and over the stretched strings, which are

thus bound in by the rising and falling of the beam. With this loom you can

also make grass or straw mats, with which to form tents or shelters, walls

or even carpets. |

|

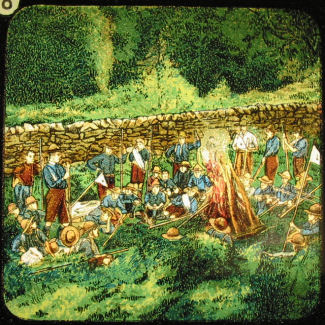

8. Round the Camp Fire.

Then in the evening twilight, we gather round the clasp fire and listen to

yarns from Baden-Powell. He talks of the boy Scouts of Mafeking; of tracking and spooring; of

reading "sign" and the value of deduction;

of

wild animals and their ways; of life on the African Veldt, or in the

backwoods; of the stars above us, and the grass beneath our feet; of

endurance, and chivalry, and life-saving-of our duty to God and man.

"Religion," says he, " is a very simple thing : 1st. To believe in God. 2nd.

'To do good to other people." We feel that he is practicing what he

preaches, and thoroughly deserves the letters of thanks that he receives

from his Scouts when Camping-days are over. Hear what one of them, a working

boy, says: "The most important thing that a great many boys need to learn is

to look at the bright side of things and to take everything by the smooth

handle. I myself found that a great lesson, and I shall never find words

enough to thank you for teaching me it. I have already found it a great help

even in everyday life." of

wild animals and their ways; of life on the African Veldt, or in the

backwoods; of the stars above us, and the grass beneath our feet; of

endurance, and chivalry, and life-saving-of our duty to God and man.

"Religion," says he, " is a very simple thing : 1st. To believe in God. 2nd.

'To do good to other people." We feel that he is practicing what he

preaches, and thoroughly deserves the letters of thanks that he receives

from his Scouts when Camping-days are over. Hear what one of them, a working

boy, says: "The most important thing that a great many boys need to learn is

to look at the bright side of things and to take everything by the smooth

handle. I myself found that a great lesson, and I shall never find words

enough to thank you for teaching me it. I have already found it a great help

even in everyday life." |

||

|

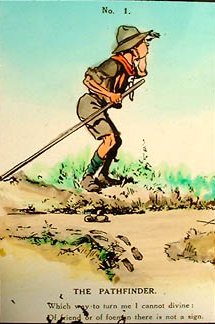

Chapter II. - CAMPAIGNING. 9. Signalling. The Scout's life is mainly campaigning, or life in the open, and signalling is a very useful branch of knowledge in this connection. So our Boy Scouts learn how to signal for long distances by means of fires - smoke fires by day, flame fires by night  -

also by means of the signal codes of the Morse and semaphore systems. In the

former of these - the "dot and flash" system - the letters are represented

by waving a flag either slowly or rapidly; in the latter, by waving your

arms at different angles to each other. Signals are also given by means of

the whistle which every Scout carries on his lanyard, by bugle call, and -

by the distinctive flags carried by the patrols - the flags which mark –

them as belonging to the "Ravens," or the "Owls," or the "Lions," or the

"Kangaroos," as the case may be. Even the Scout's pole is pressed into the

signal service, and has its meaning when held in various positions. There

are also some recognized signs-arrows, circles, etc.- to be marked on the

wall or on the ground, which mean "Gone home," "This path not to be

followed," and so on. -

also by means of the signal codes of the Morse and semaphore systems. In the

former of these - the "dot and flash" system - the letters are represented

by waving a flag either slowly or rapidly; in the latter, by waving your

arms at different angles to each other. Signals are also given by means of

the whistle which every Scout carries on his lanyard, by bugle call, and -

by the distinctive flags carried by the patrols - the flags which mark –

them as belonging to the "Ravens," or the "Owls," or the "Lions," or the

"Kangaroos," as the case may be. Even the Scout's pole is pressed into the

signal service, and has its meaning when held in various positions. There

are also some recognized signs-arrows, circles, etc.- to be marked on the

wall or on the ground, which mean "Gone home," "This path not to be

followed," and so on. |

||

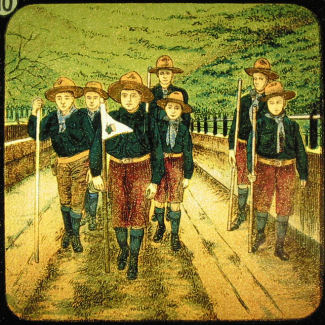

10. A Patrol on the March. Let us join a patrol of Scouts on the march. We are a party of six, besides the patrol leader – a cheery little party - and we smile and whistle as we go along, for that is a part of Scout Law. It is written in the eighth article: "A Scout smiles and whistles under all circumstances. Scouts never grouse at hardships, nor whine at each other, nor swear when put out. When you just miss a train, or someone treads on your favourite corn - not that a Scout ought to have such things as corns - or under any annoying circumstances, you should force your self to smile at once, and then whistle a tune, and you will be all right." So off we start, our patrol flag waving merrily before us; we cross a bridge, and get out into the open country, carefully noting land marks as we go along, distant hills; church towers, and nearer objects, such as peculiar buildings, trees, gates, rocks, etc. By-and-bye, we shall have to find our way hack, and then this knowledge will be useful. |

||

Persoonlijke herinneringen: Ook de verkenners kenden zo hun rituelen. We moesten elkaar een hand geven met de linkerhand, en dat terwijl mijn schooljuffrouw jarenlang haar uiterste best had gedaan mij te leren schrijven met de rechterhand. Wij moesten ook regelmatig in het gelid aantreden, gewapend met een lange stok die, zo leerden wij, overal goed voor was. Je kon er hutten mee bouwen en……. eh, ……bruggen mee bouwen, nou ja, ze waren erg nuttig in ieder geval.  Je had een patrouilleleider (PL) en een assistent-patrouilleleider (APL) en de patrouilles droegen namen van vogels, zoals de valken en de merels. Mijn patrouilleleider heette Erik Zilverentand. Dat zou in deze ‘tussen-fantasie-en-werkelijkheid-wereld’ heel goed een zelfverzonnen naam kunnen zijn geweest, maar hij was echt.  Ook uit mijn verkennertijd herinner ik mij niet meer hoe wij de middagen vulden. Het zal wel geweest zijn met….. eh… hutten bouwen. Of bruggen bouwen. Jamboreelied 1937 In negentien drie zeven. Dan zul je wat beleven: Dan komt de Jamboree in Nederland. Dan staat van alle landen, van alle ras en standen, De jeugd van blank en bruin weer hand in hand. Dan zingen scouts uit Labrador, Japan en Alkmaar Op 't Nederlands grondgebied heel vrolijk met elkaar: Jamboree, Jamboree, J.A.M.B.O.R.E.E., Jamboree, ree, ree, Jamboree, Jamboree, wij zijn verkenners van B.P.  Serie postzegels, uitgegeven t.g.v. de Jamboree in 1937. |

11. Scaling a Wall.

As we cross a common, we come across a larger body of Scouts; they are working in a

different direction to ourselves, and make a dash for a wall on our right. Over they

go, helter-skelter, and are soon lost to sight in the woods beyond. It's the

good old game of "Hare and Hounds " - only the Scouts call it "Following

the Trail." The hare is somewhere in advance, but he has certainly gone this

way; there are signs of his trail in the shape of some scraps of paper just

this side of the wall. We march on, and presently arrive at our rendezvous,

where we meet a few more fellows who will join our patrol for a game of

"Scout meets Scout." Just this side of the hill which lies away to the left

another patrol has assembled, and is working towards us. The patrol which

first sees the other will win, so now we must advance warily.

different direction to ourselves, and make a dash for a wall on our right. Over they

go, helter-skelter, and are soon lost to sight in the woods beyond. It's the

good old game of "Hare and Hounds " - only the Scouts call it "Following

the Trail." The hare is somewhere in advance, but he has certainly gone this

way; there are signs of his trail in the shape of some scraps of paper just

this side of the wall. We march on, and presently arrive at our rendezvous,

where we meet a few more fellows who will join our patrol for a game of

"Scout meets Scout." Just this side of the hill which lies away to the left

another patrol has assembled, and is working towards us. The patrol which

first sees the other will win, so now we must advance warily. |

|

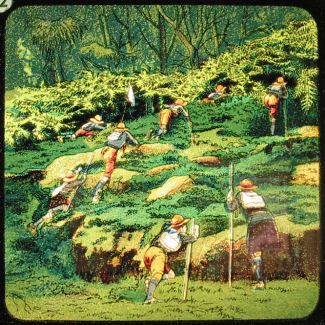

12.

Through the woods. We cross a stretch of country broken up

with rocks and

heather, and creep cautiously from one shelter to another. A Scotch fellow

has joined us, he wears a kilt instead of "shorts" like the rest of us. Now

we are through the bracken and among the trees of the wood beyond. Tread

lightly - the snapping of a dry twig may betray us to the other side if they

have got into this wood. Hide! hide! Behind the tree trunks. Evidently they

are not here, for we are through the little wood and have reached the open

fields beyond. On we go at the "Scout's pace," i.e:, walking and running

alternately from one point of cover to another. with rocks and

heather, and creep cautiously from one shelter to another. A Scotch fellow

has joined us, he wears a kilt instead of "shorts" like the rest of us. Now

we are through the bracken and among the trees of the wood beyond. Tread

lightly - the snapping of a dry twig may betray us to the other side if they

have got into this wood. Hide! hide! Behind the tree trunks. Evidently they

are not here, for we are through the little wood and have reached the open

fields beyond. On we go at the "Scout's pace," i.e:, walking and running

alternately from one point of cover to another. |

||

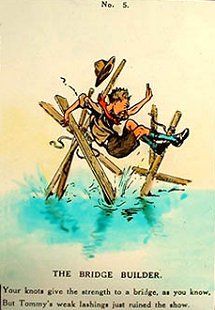

13. Look before you Leap.

We come to a little stream which we have to cross. "Look before you leap!" - it's

a good thing we did, or some of us would have got a ducking. This

brook will not check our advance, our poles soon help us across - but it

reminds us of a talk about bridges in our last Camp Fire Yarn.

Suppose

we had wanted to make a bridge? " In India, in the Himalaya mountains, the

natives make bridges out of three ropes stretched across the river and

connected together every few yards by V-shaped sticks, so that one rope

forms the footpath and the other two make the handrail on either side. They

are jumpy bridges to walk across, but they take you over and they are easily

made." We've got some bits of string among us, but they wouldn't go very far

even for a bridge like that. And we have not got an axe to fell a tree -

that's another way. However, we don't want a bridge this time - we're over;

and the other patrol is in hiding just on the other side! They see us before we have time

to shelter, so we have to admit ourselves beaten at

"Scout meets Scout." Never mind, better luck next time. Suppose

we had wanted to make a bridge? " In India, in the Himalaya mountains, the

natives make bridges out of three ropes stretched across the river and

connected together every few yards by V-shaped sticks, so that one rope

forms the footpath and the other two make the handrail on either side. They

are jumpy bridges to walk across, but they take you over and they are easily

made." We've got some bits of string among us, but they wouldn't go very far

even for a bridge like that. And we have not got an axe to fell a tree -

that's another way. However, we don't want a bridge this time - we're over;

and the other patrol is in hiding just on the other side! They see us before we have time

to shelter, so we have to admit ourselves beaten at

"Scout meets Scout." Never mind, better luck next time. |

||

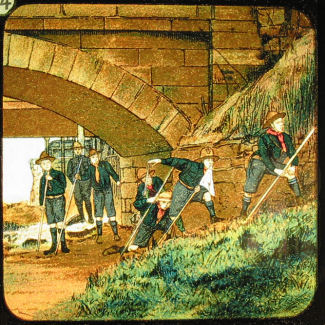

14.

Taking Shelter. Of course, when you are campaigning you have to take

things as they come. The sun does not always shine upon the Scout any more

than He does upon other people, so when you get caught in a shower you don't

grumble, but seek shelter under a hedge or a haystack, or perhaps under a

railway bridge, like this - and there you grin and bear it - or whistle and

smile, like a true Scout, until the clouds roll by and the sun comes out

again. Or perhaps you think of the Scout's motto, "Be prepared," and wish

you had brought your macintosh-especially if the rain is obstinate, and

won't stop, as is sometimes the case. But who minds a few drops of rain,

anyhow? Certainly not the Scout. 14.

Taking Shelter. Of course, when you are campaigning you have to take

things as they come. The sun does not always shine upon the Scout any more

than He does upon other people, so when you get caught in a shower you don't

grumble, but seek shelter under a hedge or a haystack, or perhaps under a

railway bridge, like this - and there you grin and bear it - or whistle and

smile, like a true Scout, until the clouds roll by and the sun comes out

again. Or perhaps you think of the Scout's motto, "Be prepared," and wish

you had brought your macintosh-especially if the rain is obstinate, and

won't stop, as is sometimes the case. But who minds a few drops of rain,

anyhow? Certainly not the Scout. |

||

15. Tea Time. The

first essential for getting some tea is to have a fire to boil the kettle,

or the "billy." Can you light a fire - not in the kitchen grate - but in the

open, and without setting fire to the grass or bush around it? Many bad

bush-fires have been caused by young tenderfoots fooling about with blazes

which they imagined to be camp fires.

Remember

then in the first place to cut away or burn all bracken, heather, grass,

etc., round the fire; and do this carefully, a little at a time, and

have branches of trees or old sacks ready

with which you can beat it out again at once when it has gone far, enough.

And as to lighting the fire itself, this is how to do it, according to Gen.

Baden-Powell: "Remember to begin your fire with a small amount of very

small chips or twigs of really dry dead wood lightly heaped together, and a

little straw or paper to ignite it; about this should be put little sticks

leaning together in the shape of a pyramid, and above this bigger sticks

similarly standing on end. When the fire is well alight bigger sticks can be

added, and, finally, logs of wood." There's a little rhyme in the book

called "Two Little ' Savages," which puts the thing very nicely: Remember

then in the first place to cut away or burn all bracken, heather, grass,

etc., round the fire; and do this carefully, a little at a time, and

have branches of trees or old sacks ready

with which you can beat it out again at once when it has gone far, enough.

And as to lighting the fire itself, this is how to do it, according to Gen.

Baden-Powell: "Remember to begin your fire with a small amount of very

small chips or twigs of really dry dead wood lightly heaped together, and a

little straw or paper to ignite it; about this should be put little sticks

leaning together in the shape of a pyramid, and above this bigger sticks

similarly standing on end. When the fire is well alight bigger sticks can be

added, and, finally, logs of wood." There's a little rhyme in the book

called "Two Little ' Savages," which puts the thing very nicely:"First a curl of birch bark as dry as it can be, Then some twigs of soft wood dead from off a tree, Last of all some pine knots to make a kettle foam, And there's a fire to make you think you're sitting right at home." Now we can get our tea, and jolly refreshing it is, when one's fagged and tired. |

||

|

Lantaarnplaten op deze pagina:

Baden Powell: 8,2

cm vierkante fotografische lantaarnplaat; |

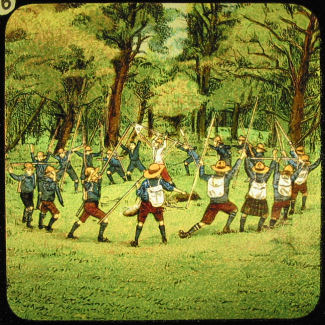

16.

Scouts' War Dance. The Scout, as we have seen, is encouraged to whistle; he is also

called upon to sing and dance. His war dance is a great sight.

The Scouts are arranged in a circle and slowly move round, singing the "Ingonyama"

song and stamping in unison on the long notes. In turn they

advance into the centre of the circle and go through a war dance, showing

how they have tracked and fought one of their enemies, or stalked and killed

a wild buffalo, the chorus going on all the time, now soft, now louder, as

the dancers get more excited. Here are the words: 16.

Scouts' War Dance. The Scout, as we have seen, is encouraged to whistle; he is also

called upon to sing and dance. His war dance is a great sight.

The Scouts are arranged in a circle and slowly move round, singing the "Ingonyama"

song and stamping in unison on the long notes. In turn they

advance into the centre of the circle and go through a war dance, showing

how they have tracked and fought one of their enemies, or stalked and killed

a wild buffalo, the chorus going on all the time, now soft, now louder, as

the dancers get more excited. Here are the words:Leader: "Een gonyâma - gonyâma." Chorus : "Invooboo, Yah bô! Yah bô! Invooboo." The meaning is : Leader; "He is a lion!" Chorus: "Yes ! he better than that : he is a hippopotamus!" No doubt this is supposed to be a great compliment; anyway, the war dance of the Scouts, seen in the fitful light of the camp fire, is just the thing to end up a day's campaigning. |

|

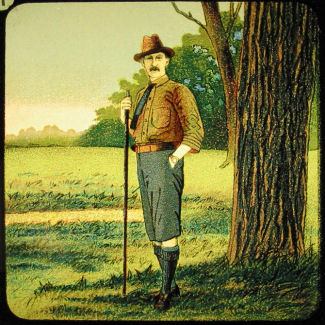

| Prachtige lantaarnplaat met het portret van Lord Baden-Powell. De afmetingen van de plaat zijn 8,2 cm x 8,2 cm) en zij is gesigneerd met 'Photo by Elliott & Fry'. |

|

| Deel 2......... | |

| |

©1997-2021 'de Luikerwaal' Alle rechten voorbehouden. Bijgewerkt tot 02-06-2021. |

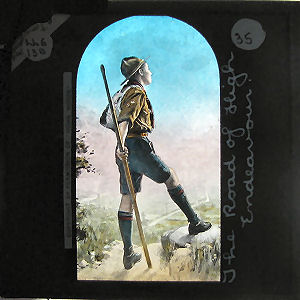

1. Lieut.-Gen. Baden-Powell, C.B.

Gen. Baden-Powell is one of the

favourites of the great British public, and especially of the younger

portion of them, the British boys. They remember how bravely he defended the

little South African town of Mafeking during the anxious days of the Boer

war: and though those days are over, and Briton and Boer have shaken hands

and are now the best of friends - he is still their hero, for has he not

started the Boy Scouts' movement? Is he not their founder, their patron,

their friend? Two years ago one had scarcely heard of the Scouts: to-day

they number 150,000 in the United Kingdom alone, and the growth of the

movement is equally remarkable in the Colonies - Canada, Australia, New

Zealand, South Africa-as well as in Germany, France and Holland. Gen.

Baden-Powell has set his heart. upon improving the boyhood of the nation,

upon training them to become good patriots and good citizens, men leading

healthy, wholesome God-fearing lives, a credit and a strength to their

native land. And so we all wish success to the Boy Scouts, and are rather

inclined to envy those fortunate few who have a chance to spend a fortnight

in camp with Baden-Powell. This portrait of the General was taken in camp,

and shows him in his campaigning outfit. The stick which he holds has an

interesting story: it was taken from a Boer farm during the days of the war.

1. Lieut.-Gen. Baden-Powell, C.B.

Gen. Baden-Powell is one of the

favourites of the great British public, and especially of the younger

portion of them, the British boys. They remember how bravely he defended the

little South African town of Mafeking during the anxious days of the Boer

war: and though those days are over, and Briton and Boer have shaken hands

and are now the best of friends - he is still their hero, for has he not

started the Boy Scouts' movement? Is he not their founder, their patron,

their friend? Two years ago one had scarcely heard of the Scouts: to-day

they number 150,000 in the United Kingdom alone, and the growth of the

movement is equally remarkable in the Colonies - Canada, Australia, New

Zealand, South Africa-as well as in Germany, France and Holland. Gen.

Baden-Powell has set his heart. upon improving the boyhood of the nation,

upon training them to become good patriots and good citizens, men leading

healthy, wholesome God-fearing lives, a credit and a strength to their

native land. And so we all wish success to the Boy Scouts, and are rather

inclined to envy those fortunate few who have a chance to spend a fortnight

in camp with Baden-Powell. This portrait of the General was taken in camp,

and shows him in his campaigning outfit. The stick which he holds has an

interesting story: it was taken from a Boer farm during the days of the war.