|

Now as with many other inventions,

for instance the art of printing, it is not known exactly who invented

the magic lantern. The 'Laterna Magica' had already been described in an old writing

by a German Jesuit priest and scientist, Athanasius Kircher.

The 1646 edition of his 'Ars magna lucis et umbrae (The great art of light

and shadow) included the description of a primitive projection system

whereby sunlight reflected off a mirror is projected through a lens on a

screen. The second edition, published in 1671, included the first drawings of a magic lantern.

There is a persistent anecdote about this erudite priest. It has to be

considered highly unlikely but it's a beautiful story after all: The father

had thought of a practical application for his invention. While visiting his unfaithful

believers in the evening, he hid a simple magic lantern under

his cowl. When talking did not help anymore, he switched to other,

tougher measures. On the glass of his lantern he had painted a realistic

image of the death, which he projected from the outside on the parchment

windows of the simple farmhouses. That was really successful and had a marked effect.

The next Sunday morning his church was packed to the very

roof again.

|

Athanasius Kircher was certainly not the first to design a magic lantern.

By the time he published his first illustrations, the magic lantern had

already been described by others, like

the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens, and was probably in fairly wide

use. In Huygens' books we find the first

description of a complete, working magic lantern and in 1659 already he

constructed a projecting lantern with a three-element lens. For that

reason Christiaan Huygens is today considered the most likely inventor of

the magic lantern.

However Christiaan was not very proud of his

invention. He was ashamed because it appeared that various swindlers were

using his instrument to frighten people. His father, who served at the

French court of Louis XIV, once ordered a lantern upon the king’s

request. Christiaan did not comply with this request because he was afraid

that he would ridicule the Huygens family. (Also read: Christiaan

Huygens, the true inventor).

|

|

|

|

|

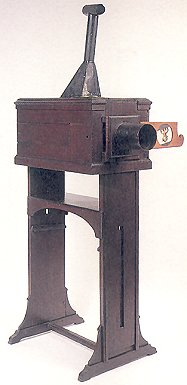

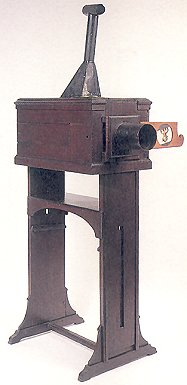

More Dutch scientists have paid an important role in the development of the magic lantern. The Professor

Willem Jacob van ‘s Gravesande, living in the Dutch town of Leiden, and the

instrument-maker Jan van Musschenbroek improved the equipment quite a

bit. (Also read: The oldest magic lantern in the

world.) At that time four-wick oil lamps came into use, whilst before mostly

a candle had been used as source of light. Van 's Gravesande's

lantern and slides survive in the Boerhaave Museum, Leiden.

|

Until the second half of the eighteenth century magic lanterns were mostly used

by scientists, but soon various people realised that it was good

business and took advantage of it. The Dutch word 'Luikerwalen'

(foreigners will probably need a long time to pronounce this word

correctly!) stands for people originating from Luik in Wallonia. They were

travelling all over the country to give performances at fairs,

in pubs etc. The government had forbidden them to carry rat-poison

throughout the country while catching rats had been the main activity of these

people to make a living before, so they had to find a new source of

income. The projector and the accompanying slides they carried on their

backs, were built by themselves in most cases.

Until the second half of the eighteenth century magic lanterns were mostly used

by scientists, but soon various people realised that it was good

business and took advantage of it. The Dutch word 'Luikerwalen'

(foreigners will probably need a long time to pronounce this word

correctly!) stands for people originating from Luik in Wallonia. They were

travelling all over the country to give performances at fairs,

in pubs etc. The government had forbidden them to carry rat-poison

throughout the country while catching rats had been the main activity of these

people to make a living before, so they had to find a new source of

income. The projector and the accompanying slides they carried on their

backs, were built by themselves in most cases.

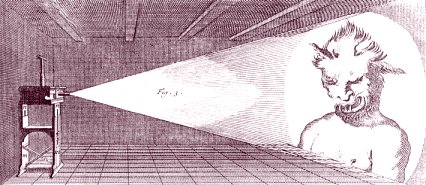

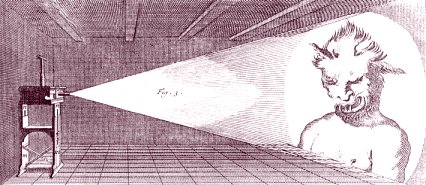

It is not likely that the misshapen person on the anonymous print from 1720 at the

left is representative of the appearance of the luikerwalen. At that

time lanternists and also hawkers on the whole were mostly portrayed as caricatures. |

|

A real rage in presenting lantern-lectures started. New, much stronger

sources of light than formerly available, made it possible to project big,

bright images for a large audience and it was also possible to project from a distance behind.

The application of limelight meant an enormous

improvement of the performance. The intense white light was produced by

heating a piece of lime, generally with a flame of combined oxygen and

hydrogen gases. Unfortunately many disasters happened due to its use. |

|

|

Besides its function in the

entertainment-world the magic lantern was used 'for teaching purposes' in

the first place. In doing so, things sometimes got seriously out of hand. In the

'Nederlandsch Magazine', No, 1 of 1863 we can read that the explorer and

missionary David Livingstone showed the local people slides of 'the wonders of creation',

but on occasion also drove the terrified African Balonda tribe

into the bush, when he presented a lantern-picture showing a life-sized

Abraham who was preparing to kill his son Isaac with a knife which he held in

his hand.

(See also: The Bible) |

|

At the end of the nineteenth century

magic lanterns with accompanying lanternslides could be found in all shops

selling scientific instruments. One of the most important outlets in the

Netherlands was Merkelbach & Co. in Amsterdam, later on a well-known

toy shop in the Kalverstraat. The family still owns a letter from the

Royal House, showing that even the little Wilhelmina (later to become

Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands) often played with her magic lantern

and with great pleasure. Mr. Merkelbach was urgently requested in this

letter to visit the palace and to bring a great number of

lantern-pictures with him, in order to exchange these for those which were

not of interest anymore. Of course there were no talks about a reasonable

financial compensation at all. It had to be for the honour alone. (Read

all about it in: Some humorous lantern

slides for the little Princess.) |

|

|

The magic lantern gradually found its way

into the living room. The types that were sold for this

purpose were much smaller than their serious brothers.

For the lighting in general a simple small oil-lamp or a candle was used.

A small funnel on top of the lantern regulated a smooth draught and the

removal of combustion gasses. The 'lampascope' was also popular, a magic

lantern with a round hole at the bottom, which could be placed over an

ordinary table-oil-lamp. Such a lamp was already available in most of the

households and by doing so an additional source of lighting was

unnecessary. To prevent the lantern tumbling forward, due to the

weight of the lens, the lid in the back part was filled with sand to make

it heavier. The appearances of the magic lanterns were quite different.

The simplest ones were made of tin plate and did not cost more than one

Dutch guilder. For people who could afford more expensive specimens

were also available; those were made of fine mahogany or were supplied with

inlaid tiles. |

|

|

The lanterns were sold

with matching glass-slides. Four or five round images

were usually printed on the glass-strips.

These often related to fairy-tale figures or subjects taken from real life. The

slides were usually sold in boxes of twelve pieces and did not cost more

than a few Dutch guilders. However they could also cost a few hundred. The

cheapest slides were covered with a sort of transfer (decalcomanias); the most expensive

ones were hand painted and placed in a wooden frame. There were real works of art

among them. |

Until the second half of the eighteenth century magic lanterns were mostly used

by scientists, but soon various people realised that it was good

business and took advantage of it. The Dutch word 'Luikerwalen'

(foreigners will probably need a long time to pronounce this word

correctly!) stands for people originating from Luik in Wallonia. They were

travelling all over the country to give performances at fairs,

in pubs etc. The government had forbidden them to carry rat-poison

throughout the country while catching rats had been the main activity of these

people to make a living before, so they had to find a new source of

income. The projector and the accompanying slides they carried on their

backs, were built by themselves in most cases.

Until the second half of the eighteenth century magic lanterns were mostly used

by scientists, but soon various people realised that it was good

business and took advantage of it. The Dutch word 'Luikerwalen'

(foreigners will probably need a long time to pronounce this word

correctly!) stands for people originating from Luik in Wallonia. They were

travelling all over the country to give performances at fairs,

in pubs etc. The government had forbidden them to carry rat-poison

throughout the country while catching rats had been the main activity of these

people to make a living before, so they had to find a new source of

income. The projector and the accompanying slides they carried on their

backs, were built by themselves in most cases.