|

|

||||||||||

| Naar: | deel 1 | deel 2 | deel 3 | deel 4 | deel 5 | deel 6 | deel 7 | deel 8 | deel 9 | deel 10 |

|

|

||||||||||

|

Gabriel Grub

of The story of the goblins who stole a sexton De geschiedenis van de kobolds die een doodgraver ontvoerden. |

||

|

In 1836,

zeven jaar voordat hij A Christmas Carol schreef, publiceerde Charles Dickens 'The Story

of the Goblins who stole a Sexton' als Hoofdstuk 29 van The Pickwick Papers.

Dit korte verhaal dat oorspronkelijk tussen maart 1836 en oktober 1837 gepubliceerd werd als een feuilleton, gaat over de vreemde belevenissen van Gabriel Grub,

de koster/doodgraver van een kerk in een klein, landelijk dorp, die een

familielid zou kunnen zijn van Ebenezer Scrooge. Dickens beschrijft Gabriel Grub als

'een dwarsche, norsche, kwaadaardige kerel - een stuursch en ongezellig man, die

met niemand dan met zich zelven en met een oud matten fleschje, dat in zijnen

grooten broekzak volkomen paste, omging, - en die elk vrolijk gelaat in het

voorbijgaan zóó boosaardig aangrijnsde, dat men vreesde, dat hij het er niet bij

zoude laten, dat men onwillekeurig aan het graf dacht.' *) Hij had 'een

dreigende blik vol boosaardigheid en slecht humeur.' Dat doet behoorlijk aan Scrooge

denken, nietwaar? In het boek vertelt iemand ‘The Story of The Goblins Who Stole a Sexton’ waarin Gabriel Grub op de avond voor Kerst een graf aan het graven is en bezoek krijgt van kobolds. Zij trekken hem onder de aardbodem om hem naar hun koning te brengen. De kobolds laten Gabriel een serie taferelen zien, totdat hij tot de conclusie komt dat 'het toch uiteindelijk wel een erg aardige en achtenswaardige wereld was waarin hij leeft' . |

||

| *) bron: De Gids. Jaargang 1. | ||

|

'De toverlantaarnplaten. |

||

|

|

|

|

Introduction Introductie |

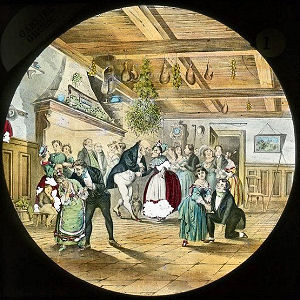

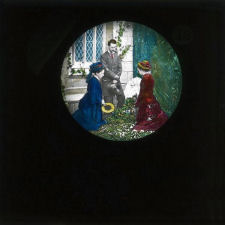

1 Kissing under the mistletoe Kussen onder de maretak |

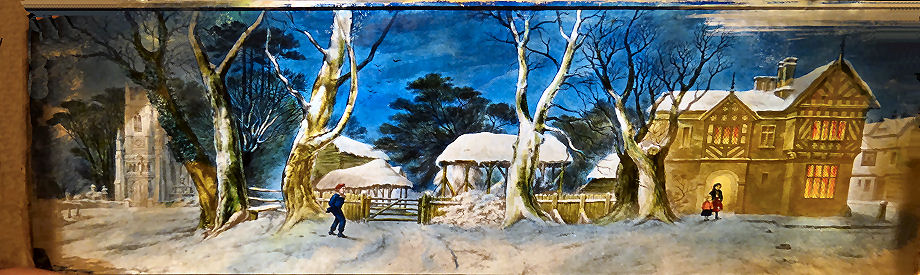

2 Panorama -- An old Abbey Town Panorama - Een oud Abdijstadje |

|

|

|

|

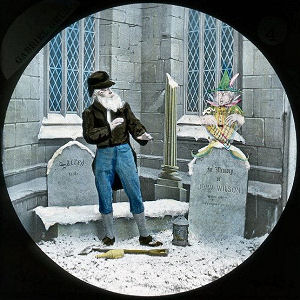

3 He sat himself down on a flat tombstone Hij ging zitten op een platte grafsteen |

4 Close to him was a strange unearthly figure Dicht bij hem was een vreemde onaardse gedaante |

5 Playing at leapfrog with the tombstones Zij speelden haasje-over tussen de grafstenen |

|

|

|

|

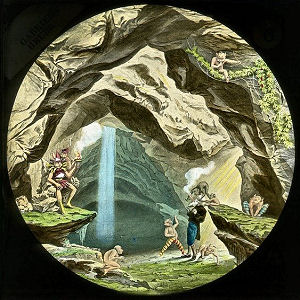

6 He found himself in a large dark cavern Hij ontdekte dat hij zich in een grote donkere grot bevond |

7 A thick cloud rolled gradually away Een dikke wolk rolde geleidelijk aan weg |

8 A crowd of little children were gathered round Een stel kleine kinderen was daar bijeen |

|

|

|

|

9 He was wet and weary Hij was nat en vermoeid |

10 Then he sat down to his meal Toen hing hij zitten voor de maaltijd |

11 The fairest and youngest child lay dying Het liefste en jongste kind lag op sterven |

|

|

|

|

12 The father and mother were old and helpless now De vader en moeder waren nu machteloos |

13 The few who had survived then knelt by their tomb De paar die het hadden overleefd knielden bij het graf |

14 A rich and beautiful landscape was disclosed Een overvloedig en prachtig landschap werd geopenbaard |

|

|

|

|

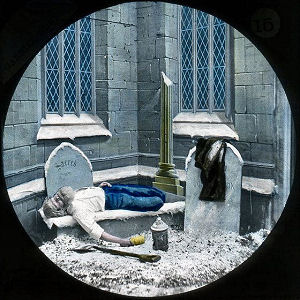

15 Lying at full length on the tombstone In zijn volle lengte lag hij op de grafsteen |

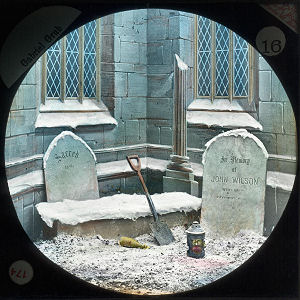

16 The lantern, the spade, and the wicker bottle De lantaarn, de spade en zijn 'matten' flesje |

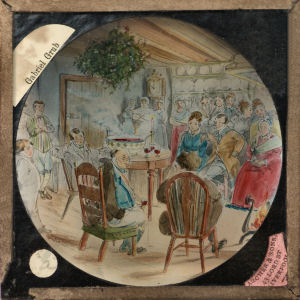

17 He told his story to the Clergyman and to the Mayor Hij vertelde zijn verhaal aan de priester en aan de burgemeester |

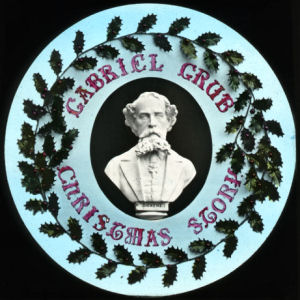

De

serie bestaat uit 17-19 lantaarnplaten en werd geproduceerd door York & Son, England, ca 1875.

Op plaat nummer 17 herkennen we Frederick York, de oprichter van het bedrijf, in

de rol van de Burgemeester. De platen zijn met de hand gekleurd en meten 8,2 x

8,2 cm. Etiketten op de plaat: 'Gabriel Grub', het nummer van de plaat en het

handelsmerk van de fabrikant York and Son, een 'Y' met een daaromheen

gestrengelde slang. De

serie bestaat uit 17-19 lantaarnplaten en werd geproduceerd door York & Son, England, ca 1875.

Op plaat nummer 17 herkennen we Frederick York, de oprichter van het bedrijf, in

de rol van de Burgemeester. De platen zijn met de hand gekleurd en meten 8,2 x

8,2 cm. Etiketten op de plaat: 'Gabriel Grub', het nummer van de plaat en het

handelsmerk van de fabrikant York and Son, een 'Y' met een daaromheen

gestrengelde slang. |

||

|

In te voegen lantaarnplaten. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

De platen 8 - 14 zijn

overvloeiers, gebruikt om in te voegen in de

plaat nummer 7. Dat geeft dan een indruk van de tableaus die Gabriel zag toen

hij in de grot was en een dikke wolk opzij schoof. In het oorspronkelijke

verhaal is dit een reeks geanimeerde visioenen, niet met elkaar verbonden door

tijd of plaats, die met elkaar werden verbonden door iets wat doet denken aan

een optische voorstelling met overvloeiers: 'Nogmaals gleed een lichte wolk over

wat hij zag en opnieuw veranderde het onderwerp.' Dat klinkt toch helemaal alsof

het een toverlantaarnvoorstelling betrof, nietwaar?

|

|||

|

|

||

|

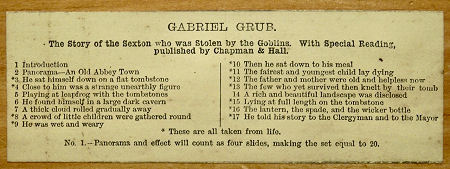

Houten kistje van 28,5 x 12,5 x 6 cm met de vierkante lantaarnplaten van 8,3 x 8,3 cm en een langwerpige plaat (de panoramaplaat #2) in een houten frame van 26 cm lang. Aan de binnenkant van het deksel een etiket met de titels van de 17 lantaarnplaten. |

||

|

|||

|

|

|

|

De originele Reading (het bijgesloten tekstboekje) van Gabriel Grub. Ik kon mij er niet toe zetten deze Readings te vertalen naar het Nederlands. Dat is ook niet nodig want het complete verhaal vindt u in De Gids, jaargang 1. |

||

|

CHRISTMAS TIME! That man must be a misanthrope indeed in whose breast something like a jovial feeling is not roused, in whose mind some pleasant associations are not awakened by the recurrence of Christmas. A Christmas family party! We know nothing in nature so delightful Happy happy Christmas! that can win us back to the delusions of our childish days, that can recall to the old man the pleasures of his youth, that can conjure up the old house, the room, the merry voices and smiling faces. The jest, the laugh, the most minute circumstances connected with those happy meetings crowd upon our mind at each recurrence of the season as it the last assemblage had been but yesterday Few among modern writers can be compared with Dickens in delineating he dearly cherished festivals of his countrymen; a description of Christmas and its social . festive from his graphic pen are pictures few can imitate and none surpass; his own genial nature gushed forth in every line, and we can almost imagine that we hear the joyous laughter of a jolly Christmas party as one reads the story. Among the many sketches of an old-fashioned Christmas gathering from the pen of the deeply lamented author, perhaps the most humorous is that which occurs in the "Pickwick Papers," where the immortal Pickwick and his travelling companions - Tupman, Snodgrass. and Winkle - pay a visit to the hospitable residence of that jolly and benevolent specimen of English squires, Mr. Wardle, on the occasion of his daughter's marriage, which was fixed to take place on a 24th of December; unfortunately the figures denoting the year have become obliterated in the records of the club, but it may be safely conjectured sometime between 1800 and 1825. [B] Out story opens on the evening of the eventful day. | |

|

No. 1 - INTRODUCTION The best kitchen at Manor House was a good long dark panelled room with a high chimney piece, and a capacious chimney, up which you could have driven one of the new patent cabs, wheels and all. The candles burnt bright; the fire blazed and crackled on the hearth; and merry voices and light-hearted laughter rang through the room. If any of the old English Yeomen had turned into fairies when they died, it was just the place where they would have held their revels. From the centre of the ceiling, old Mr. Wardle had just suspended a huge branch of mistletoe, and, if the story is to be believed, the gallant My Pickwick had led the venerable Mrs Wardle, the mother of the host, beneath the mystic branch, and saluted her with all courtesy and decorum. The old lady submitted to this piece of practical politeness with all the dignity which befitted so important and serious a solemnity; but the younger ladies screamed, and struggled, and ran into corners, and threatened and remonstrated, and did everything but leave the room; when all at once they found it useless to resist any longer, and submitted to be kissed with good grace. When they were all tired of blind man's buff, snap dragon, and other boisterous games, they sat down by the huge fire of blazing logs to enjoy a mighty bowl of wassail, in which the hot apples were hissing and bubbling with a rich look and a jolly sound that were perfectly irresistible. "This," said Mr Pickwick, looking round him, "this is indeed comfort " "Our invariable custom," replied Mr. Wardle "everybody sits down with us on Christmas eve - servants and all - and here we wait until the clock strikes twelve to usher Christmas in, and we beguile the time with forfeits and old stories. "How it snows!" said one of the men in a low tone. "Snows! Does it?" said Wardle. "Rough, cold night, sir," replied the man, "and there's a wind got up that drifts across the fields in a thick white cloud." "Ah," said the old lady, "there was just such a wind, and just such a fall of snow, just five years before your poor father died. It was a Christmas eve too, and I remember that on that night he told us the story about the goblins that carried away old Gabriel Grub." "The story about what?" said Mr. Pickwick. "Oh nothing, nothing" replied Wardle, "about an old sexton that the good people down here supposed to have been carried away by ' goblins." "Suppose!" ejaculated the old lady, "is there anybody hardy enough to believe it. Suppose! Haven't you heard ever since you were a child that he was carried away by goblins, and don't you know he was?" "very well, mother, he was, if you like," said Wardle laughing. "He was carried away by goblins, Pickwick; and there’s an end of the matter." [B] "No, no" said Mr Pickwick, "not an end of it, I assure you; for I must hear how, and why, and all about it. So, ladies and gentlemen, a clear stage and no favour for Mr Wardle and the goblins." STORY. No. 2 - PANORAMA - AN OLD ABBEY TOWN In an old Abbey town down in this part of the country, there officiated as sexton and grave-digger in the church-yard, one Gabriel Grub. It by no means follows that because a man is a sexton and constantly Surrounded by emblems of mortality, therefore, he should be a morose and a melancholy man; undertakers are amongst the merriest fellows in the world, and mutes, when off duty, will crack jokes and sing comic ditties that would make a bishop dance, in spite of his dignity. But notwithstanding these precedents to the contrary, Gabriel Grub was an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow. He was short, cadaverous and withered. His throat, chin, and eyebrows, so posted with white hairs, and so gnarled with veins, and puckered skin, that he looked, from his breast upwards, like some old root in a fall of snow. He was invariably clothed in a suit of rusty black, and looked as if the garments had been stolen from the corpse of some suicide; he consorted with nobody but himself and an old wicker-bottle, which he invariably carried in a huge breast pocket. He eyed each merry face as it passed with such a deep scowl of malice and ill-humour, as it was difficult to meet, without feeling something the worse for. A little before twilight one Christmas eve, Gabriel shouldered his spade, lighted his lantern, and betook himself towards the old churchyard, for he had got a grave to finish by next morning, and feeling very low, he thought it might raise his spirits, perhaps, if he went on with his work at once. As he went his way up the ancient street, he saw the cheerful light of the blazing fires gleam through the old casements, and heard the loud laugh and the cheerful shouts of those who were assembled around them; he marked the bustling preparations for the next day's cheer, and smelt the numerous savoury odours consequent there from, as they steamed. from the kitchen windows in clouds. All this was gall and wormwood to the heart of Gabriel Grub; and when groups of children bounded out of the houses, tripped across the road and were met, before they could knock at the opposite door, by half-a-dozen curly-headed little rascals who crowded round them as they flocked upstairs to spend the evening in their Christmas games, Gabriel smiled grimly, and clutched the handle of his spade with a firmer grasp as he thought of measles, scarlet fever, thrush, whooping cough, and a good many other sources of consolation besides. In this happy frame of mind Gabriel strode along, returning a short sullen growl to the good humoured greetings of such of his neighbours as now and then passed him, until he turned into the dark lane which led to the churchyard. Now, Gabriel had been looking forward to reaching the dark lane, because it was, generally speaking, a nice, gloomy, mournful place, into which the towns-people did not much care to go, except in broad daylight and when the sun was shining; consequently, he was not a little indignant to hear a young urchin roaring out some jolly song about a merry Christmas in this very sanctuary, which had been called Coffin Lane ever since the days of the old abbey and the time of the shaven-headed monks. As Gabriel walked on, and the voice drew nearer, he found it proceeded from a small boy who was hurrying along to join one of the little parties in the old street, and who, partly to keep himself company, and partly to prepare himself for the occasion, was shouting out the song at the highest pitch of his lungs. So Gabriel waited until the boy came up, and then threatened him with a severe drubbing, if he did not at once leave off making such a noise. And as the boy hurried away with this angry admonition ringing in his ear, Gabriel Grub chuckled very heartily to himself, and entered the churchyard, locking the gate behind him. He took off his coat, put down his lantern, and getting into the unfinished grave, worked at it for an hour or two with right good will. But the earth was hardened with the frost, and it was no very easy matter to break it up and shovel it out; and although there was a moon, it was a very young one, and shed little light upon the grave, which was in the shadow of the church. At any other time these obstacles would have made Gabriel Grub very moody and miserable; but he was so well pleased with having stopped the small boy's singing, that he took little heed of the scanty progress he had made, and looked down into the grave when he had finished work for the night with grim satisfaction, murmuring, as he gathered up his things: [B] "Brave lodgings for one - brave lodgings for one - A few feet of cold earth when life is done; A stone at the head, a stone at the feet, A rich juicy meal for the worms to eat! Rank grass overhead and damp clay around, Brave lodgings for one, there, in holy ground!" No. 3 - HE SAT HIMSELF DOWN UPON A FLAT TOMBSTONE "Ho! ho!" laughed Gabriel Grub, as he sat himself down on a flat tombstone which was a favourite resting place of his, and draws forth his wicker bottle. "A coffin at Christmas! A Christmas box! Ho! ho! ho!" "Ho! ho! ho!" repeated a voice, which sounded close behind him. Gabriel paused in some alarm, in the act of raising the wicker bottle to his lips, and looked around. The bottom of the oldest grave about him was not more still and quiet than the churchyard in the pale moonlight. The cold hoar frost glistened on the tombstones, and sparkled like rows of gems among the stone carvings of the old church. The snow lay hard and crisp upon the ground, and spread over the thickly-strewn mounds of earth, so wide and smooth a cover that it seemed as if the corpses lay there hidden only by their winding sheets. Not the faintest rustle broke the profound tranquillity of the solemn scene. Sound itself appeared to be frozen up, all was so cold, and still. [B] "It was the echoes," said Gabriel Grub, raising the bottle to his lips again." It was not," said a deep voice. No. 4 - CLOSE TO HIM WAS A STRANGE UNEARTHLY FIGURE Gabriel started up and stood rooted to the spot with astonishment and terror, for his eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold. Seated on an upright tombstone close to him was a strange unearthly figure, whom Gabriel felt at once was no being of this world. His long fantastic legs, which might have reached the ground, were cocked up, and crossed after a quaint fantastic fashion; his sinewy arms were bare; and his hands rested on his knees. On his short round body he wore a close covering, ornamented with small slashes; a short cloak dangled at his back; the collar was cut into curious peaks, which served the goblin in lieu of ruff or neckerchief; and his shoes curled up at his toes into long points. On his head he wore a broad-brimmed sugar-loaf hat, garnished with a single feather. The hat was covered with the white frost; and the goblin looked as if he had sat on the same tombstone very comfortably for two or three hundred years. He was sitting perfectly still; his tongue was. put out as if in derision, and he was grinning' at Gabriel Grub with such a grin as only a goblin could call up. "It was not the echoes," said the goblin. Gabriel Grub was paralysed, and could make no reply .- "What do you here on Christmas eve?" said the goblin sternly. "I came to dig a grave, sir," stammered Gabriel Grub. "What man wanders among graves and churchyards on such a night as this?" cried the goblin. "Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub!" screamed a wild chorus of voices that seemed to fill the churchyard. Gabriel looked tearfully around - nothing could be seen. "What have you got in that bottle?" said the goblin. "Hollands, sir," replied the sexton, trembling more than ever, for he had bought it of the smugglers, and he thought that perhaps his questioner might be in the excise department of the goblins. "Who drinks Hollands alone and in a churchyard, on such a night as this ?" said the goblin. "Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub," exclaimed the wild voices again. The goblin leered maliciously at the terrified sexton, and then, raising his voice, exclaimed - "And who, then, is. our fair and lawful prize?" To this inquiry the invisible chorus replied, in a strain that sounded like the voices of many choristers singing to the mighty swell of the old church organ - a strain that seemed borne to the sexton's ears upon a wild wind, and to die away as it passed onwards; but the burden of reply was still the same - "Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub," The goblin grinned a broader grin than before, as he said, " Well, Gabriel, what do you say to this ?" The sexton gasped for breath. '" What do you think of this, Gabriel ? " said the goblin, kicking up his feet in the air on either side of the tombstone, and looking at the up-turned points with as much complacency as if he had been contemplating the most fashionable pair of Wellingtons in all Bond Street. " It's - it's - very curious, sir," replied the sexton, half dead with fright, " very curious and very pretty, but I think I'll go back and finish my work, sir, if you please." " Work! " said the goblin, " what work ? " " The grave, sir; making the grave," stammered the sexton. " Oh, the grave, eh ? " said the goblin, " who makes graves at a time when all other men are merry, and takes a pleasure in it ? " Again the mysterious voices replied-" Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub! " " I'm afraid my friends want you, Gabriel," said the goblin, thrusting his tongue further into his cheek than, ever -and a most astonishing tongue ft was-" I'm afraid my friends want you, Gabriel," said the goblin. " Under favour, sir," replied the horror stricken sexton, "I don't think they can, sir; they don't know me, sir; I don't think the gentle- men have ever seen me, sir." " Oh, yes, they have," replied the goblin; "we know the man with the sulky face and grim scowl that came down the street to- night, throwing his evil looks at the children, and .grasping hid burying spade the tighter. We know the man who scolded the boy in the envious malice of his heart, because the boy could be merry and he could not. We know him - we know him." Here the goblin gave a loud shrill laugh, which the echoes returned twenty-fold; and throwing his legs up in the air, stood upon his head, or rather upon the very point of his sugar-loaf hat on the narrow edge of the tombstone,, whence he threw a somersault with extraordinary agility right to the sexton's feet, at which he planted himself in the attitude in which tailors generally sit . upon the shop board. [B] " I-I-am afraid I must leave you, sir," said the sexton, making an effort to move. " Leave us! " said the goblin; " Gabriel Grub going to leave us! Ho! ho! ho! " No. 5 - PLAYING AT LEAPFROG WITH THE TOMB- STONES As the goblin laughed, the sexton observed, for one instant, a bright illumination within the windows of the church, as if the whole building were lighted up; it disappeared, the organ pealed forth a lively air, and whole troops of goblins, the very counter- part of the first one, poured into the churchyard, and began playing at leapfrog with the tombstones, never stopping for an instant to take breath, but "ovaring" the highest among them, one after the other, with the utmost marvellous dexterity. The first goblin was a most astonishing leaper, and none of the others could come near him; even in the extremity of his terror the sexton could not help observing that while his friends were content to leap over the common-sized gravestones, the first one took the family vaults - iron railings and all, with as much ease as if they had been so many street posts. At last the game reached to the most exciting pitch; the organ played quicker and quicker and the goblins leaped faster and faster, coiling themselves up rolling head over heels upon the ground, and bounding over the tombstones like footballs. The sexton's brain whirled round with the rapidity of the motion he beheld, and his legs reeled beneath him as the spirits flew before his eyes [B] when the goblin king, suddenly darting towards him, laid his hand upon his collar, and sank with him through the earth. No. 6 - HE FOUND HIMSELF IN A LARGE DARK CAVERN When Gabriel Grub had had time to fetch his breath, which the rapidity of his descent had for a moment taken away, he found himself in what appeared to be a large cavern, surrounded on all sides by goblins ugly and grim. In the centre of the vault, on an elevated seat, was stationed his friend of the church-yard, and in front of the rude platform stood Gabriel Grub himself, without power of motion. "Cold tonight," said the king of the goblins; "very cold. A glass of something warm here!" At this command half-a-dozen officious goblins, with a perpetual smile upon their faces, whom Gabriel Grub imagined to be courtiers on that account, hastily disappeared, and presently returned with a goblet of liquid fire, which they presented to the king. "Ah!" cried the goblin, whose cheeks and throat were transparent as he tossed down the flame, "this warms one indeed! Bring a bumper of the same for Mr. Grub!" It was in vain for the unfortunate sexton to protest that he was not in the habit of taking anything warm at night. One of the goblins held him, while another poured the blazing liquor down his throat. The whole assembly screeched with laughter as he coughed and choked, and wiped away the tears which gushed plentifully from his eyes after swallowing the burning draught. [B] "And now," said the king, fantastically balancing his sugar-loaf hat on the points of his snake-like fingers: " and now, show the man of misery and gloom a few of the pictures from our great storehouse." No. 7 - A THICK CLOUD ROLLED GRADUALLY AWAY As the goblin said this, a thick cloud, which obscured the remoter end of the cavern, rolled gradually away, [B] and disclosed, apparently at a great distance, the vision of a small and scantily-furnished, but clean and neat apartment, evidently belonging to that struggling class among (business) men - the poor clerk (teacher). On the table was spread a frugal meal. No. 8 - A CROWD OF LITTLE CHILDREN WERE GATHERED ROUND The anxious mother was seated near the window, surrounded by a group of children. On her lap lay the darling of the poor but happy family. The wan and pinched features of the suffering child were sure indexes of what was passing in the distressed mother’s heart as she was watching the wasting away of her child. [B] The eldest boy was peering into the frosty street, expecting the return of the father, for whom the arm chair had been placed close to the cheerful fire. No. 9 - HE WAS WET and WEARY A knock is heard at the outer door, and a new picture came before the gaze of the bewildered sexton. The tired father had entered the apartment, and was soon surrounded by his lowly but affectionate family. [B] Even the1 sick child had a smile for dear father; and each of the elder ones, with busy zeal, had seized the coat and hat and stick, to carry them from the room. No. 10 - THEN HE SAT DOWN TO HIS MEAL The vision again changed, and a new scene gradually came into view. The weary man had partaken of the frugal meal, and, warmed by the cheering influences of home and its dearly cherished inmates, he was recounting the adventures of the day. [B] Contentment was depicted on each countenance, as wife and children listened to the father's story. No. 11 - THE FAIREST AND YOUNGEST CHILD LAY DYING Presently the picture began to fade away, and the scene was altered to a small bedroom, where the fairest and youngest child lay dying. The roses had fled from its cheek, and the light from its eye. His brother and sisters crowded around his little bed, and seized his tiny hand, so cold and heavy. But they shrank back from its touch, and looked with awe on its infant face; for, calm and tranquil as it was, and sleeping in rest and peace as the beautiful child seemed to be, they saw that it was dead, and they knew that he was an angel, looking down and blessing them from a bright and happy heaven. [B] The sexton looked upon the picture with an interest and with feelings he had never experienced, or known before. No. 12 - THE FATHER AND MOTHER WERE OLD AND HELPLESS NOW Again the light cloud passed across the picture, and again the subject changed. The father and mother are old and helpless now, and the number of those about them was. diminished more than half; but content and cheerfulness sat on every face,. and beamed in every eye, [B] as they crowded round ' the fireside, and told and listened to old stories of earlier and bygone days. No. 13 - THE FEW WHO YET SURVIVED THEM KNELT BY THEIR TOMB A deeper shadow began to gather over the picture, and eventually the outline of a churchyard, with its memorials of the dead, came upon the scene. Slowly and peacefully the father had sunk into the grave, and soon after the sharer of all his care and troubles followed him to a place of rest. The few who had survived them knelt by their tomb, and watered the green turf which covered it with their tears; but not with bitter cries or despairing lamentations, for they knew that they should one day be meeting again. The cloud settled upon the picture, and concealed it from the sexton's view. " What do you think of THAT ? " said the goblin, turning his large face toward Gabriel Grub. Gabriel murmured out something about its being very pretty, and looked somewhat ashamed as the goblin bent his fiery eyes upon him. " You, a miserable man!" said the goblin in a tone of excessive contempt, " You! " He appeared disposed to add more, but indignation choked his utterance. He lifted up his ' pliable legs as if for a signal, when on an instant poor Gabriel Grub was the butt for a series of kicks and pinches, administered by a host of invisible goblins-in- waiting, who buzzed and tormented the wretched sex- ton without mercy - obeying the invariable custom of courtiers on earth, who kick who royalty kicks, and hug whom royalty hugs. "Show [B] him some more," said the king of the goblins. No. 14.--A RICH AND BEAUTIFUL LANDSCAPE WAS DISCLOSED At these words, the cloud was dispelled and a rich and beautiful landscape was disclosed to view - there is just such another today - within half-a-mile of the old abbey town. The sun shone from out the clear blue sky; the water sparkled beneath his rays; and the trees looked greener, and the flowers more gay, beneath his cheering influence. The water rippled on with a pleasant sound; the trees rustled, in the light wind that murmured among their leaves; the birds sang upon the boughs; and the lark carolled on high, her welcome to the morning. Yes, it was morning - the bright balmy morning of summer. The minutest leaf, the smallest blade of grass, was instinct with life. The ant crept forth to her daily toil; the butterfly fluttered, and basked in the warm rays of the sun; myriads of insects spread their transparent wings and revelled in their brief but happy existence; man walked forth elated with the scene, and all was brightness and splendour. "You a miserable man!" said the king of the goblins, in a more contemptuous tone than before; and again the king of the goblins gave the signal by a. flourish of his legs, and again the attendant goblins inflicted their torments on the body of the miserable sex- ton. Many a time the cloud went and came, and many a lesson it taught to Gabriel Grub, who, although his arms and legs smarted with pain from the cuffs and pinches of his merciless tormentors, looked on each passing scene with an interest nothing could diminish. He saw that men who worked hard, and earned their scanty bread with lives of labour, were cheerful and happy. He saw those who had been delicately nurtured and tenderly brought up, cheerful under privation and superior to suffering. He saw that women, the tenderest and most fragile of all God’s creatures, were the oftenest superior to sorrows, adversity, and distress; and he saw that it was because the bore in their own hearts an inexhaustible well-spring of affection and devotion. Above all, he saw that men like himself, who snarled at the mirth and cheerfulness of others, were the foulest weeds on the fair surface of the earth. And setting all the good of the world against the evil, he came to the conclusion that it was a very decent and respectable sort of world, after all. No sooner had he formed it that the cloud which closed over the last picture seemed to settle on his senses, and lull him to repose. [B] One by one the goblins faded from his sight, and as the last one disappeared he sank to sleep. No. 15 - LYING AT FULL LENGTH ON THE TOMB- STONE The day had broken when Gabriel Grub awoke and found himself lying at full length on the flat grave- stone in the churchyard, and the wicker-bottle lying empty at his side, and his coat, spade, and lantern, all well whitened by the last night's frost scattered on the ground. The stone on which he had first seen the, goblin stood bolt upright before him; and the grave at which he had worked the night before was not far off. " At first he began to doubt the reality of his adventures, but the acute pain in his limbs, when he attempted to rise, assured him that the pinching and cuffs of the goblins were certainly not ideal. He was staggered again by observing no traces of footprints in the snow on which the goblins had played at leapfrog with the grave-stones, but he speedily accounted for this circumstance when he remembered that, being spirits, they would leave no visible impression behind them. So Gabriel Grub got on his feet as well as he could, for the pain in his back; and, brushing the frost off his coat, put it on, and turned his face towards the town. But he was an altered man, and he could not bear the thought of returning to a place where his repentance would be scoffed at, and his reformation disbelieved [BJ He hesitated for a few moments, and then turned away to wander where he might, and seek his bread elsewhere. No. 16 - THE LANTERN, THE SPADE, AND THE WICKER BOTTLE The lantern, the spade, and the wicker bottle were found that day in the churchyard. There were a great many speculations about the sexton's fate at first, but it was speedily determined that he had been carried away by the goblins; and there was not wanting some very credible witnesses who had distinctly seen him whisked through the air on the back of a chestnut horse, blind of one eye, with the hind quarters of a lion and the tail of a bear. At length all this was devoutly believed, and the new sexton used to exhibit to the curious, for a trifling emolument, a good-sized piece of the church weather cock [B] which had been accidentally been kicked off by the aforesaid horse in his aerial flight, and picked up by himself in the churchyard a year or two afterwards! No. 17 - HE TOLD HIS STORY TO THE CLERGYMAN AND TO THE MAYOR Unfortunately, these stories were somewhat disturbed by the unlooked for re-appearance of Gabriel Grub himself, some ten years afterwards, a ragged, contented, rheumatic old man. He told his story to the clergyman, and also to the mayor; and in course of time it began to be received as a matter of history, in which form it has continued down to this very day. The believers in the weathercock tale, having misplaced their confidence once, were not easily prevailed upon to part with it again, so they looked as wise as they could, shrugged their shoulders, touched their foreheads, and murmured something about Gabriel Grub having drunk all the Hollands, and then fallen asleep on the flat tombstone; and that they affected to explain what he supposed he had witnessed in the goblins’ cavern, by saying that he had seen the world and grown wiser. But this opinion, which was by no means a popular one at any time, gradually died off, and, be the matter how it may, Gabriel Grub was afflicted with rheumatism to the end of his day. This story has at least one moral, if it teaches no better one, and that is, that if a man turn sulky, and drink by himself at Christmas time, he may make up his mind to be not a bit the better for it; let spirits be never so good, or let them be even as many degrees beyond proof as those which Gabriel Grub saw in the goblins’ cavern. The end. |

||

|

Het einde. |

||

Tot slot een heel vroege toverlantaarnplaat met Gabriel Grub uit een set die gemaakt of verkocht is door Archer & Son, Liverpool, Engeland. Met de hand geschilderd. |

|

|

|

Meer Dickens...... |

| |

©1997-2023 'de Luikerwaal' Alle rechten voorbehouden. Bijgewerkt tot 12-08-2023. |

|