|

It is poignant that there has hardly been any research into the use of the magic lantern in the Netherlands

until now. In children’s

literature from the 19e century as well as descriptions from -for instance-

fairs and feasts, the magic lantern is mostly only indirectly mentioned. Only Marieke de Natris (Kčkt nâh – a

research into the use of the

magic lantern in the Netherlands in the context of visual media, Master's exam,

Leiden - 2002), and Vera Tietjens-Schuurman

(Van toverlantaarn tot kinematograaf - Rottevalle 1979) examined this matter in great detail. |

|||

|

An important role for the Dutch Quite a few Dutchmen played an important role in the development of the Magic Lantern as well as the design of (mechanical) lantern slides in the 17th and 18th century. In particular it was the scientist, Christiaan Huygens  who played a crucial part in the invention of the Laterna Magica. As from 1653

Huygens experimented with lenses, microscopes and telescopes. In 1659 he

described the working of his magic lantern provided with three lenses, intended

to amuse his children at home. Huygens did not show off this invention. When the

French Court was interested in a performance with Huygen's lantern he wrote:

"I am ashamed because it will transpire that the device is mine." who played a crucial part in the invention of the Laterna Magica. As from 1653

Huygens experimented with lenses, microscopes and telescopes. In 1659 he

described the working of his magic lantern provided with three lenses, intended

to amuse his children at home. Huygens did not show off this invention. When the

French Court was interested in a performance with Huygen's lantern he wrote:

"I am ashamed because it will transpire that the device is mine."A friend of Huygens, the Dutch Jesuit Andreas Taquet, possibly gave the first 'magical' performance for an audience about this time. Other Dutch pioneers of the lantern were the brothers P. and J. van Musschenbroek and the learned professor and physicist W. J. ‘s Gravensande.  Jan van Musschenbroek constructed for 's Gravensande a

man-sized magic lantern in Leiden

around 1720. Some years later Jan van Musschenbroek made some mechanical lantern

slides that were shown by his brother Petrus in 1731. In 1739 Petrus described

several mechanical movable lantern slides. By means of turning, pulling, or

the use of a level, two glass discs were enabled to move in front of each other (sails of

a windmill start to turn, a gentleman takes off his hat, a cow takes a dog on

its horns, a shoemaker moves his hammer). Jan van Musschenbroek constructed for 's Gravensande a

man-sized magic lantern in Leiden

around 1720. Some years later Jan van Musschenbroek made some mechanical lantern

slides that were shown by his brother Petrus in 1731. In 1739 Petrus described

several mechanical movable lantern slides. By means of turning, pulling, or

the use of a level, two glass discs were enabled to move in front of each other (sails of

a windmill start to turn, a gentleman takes off his hat, a cow takes a dog on

its horns, a shoemaker moves his hammer). |

|||

|

Prime of the magic lantern The prime time of the magic lantern is from about 1840 until about 1900, also in the Netherlands. This is mainly thanks to a number of technical improvements: better sources of light (lime light, paraffin lamps, gas light, and finally electrical light), better objectives, the production of large amounts of lantern slides, photographical positives on glass. Large lanterns, often provided with two or three lenses above each other, make it possible to give lantern shows for hundreds of spectators at the same time. By the use of more lenses in a lantern also dissolving views and chromatropes or colour changers became possible.  In the latter half of the 19th century well into the 20th century,

the lantern’s domestic use was flooded by a new market: the toy lantern, bought

especially for children. In

the Netherlands toy lanterns were mainly bought from the German manufacturers

Ernst Plank and the Bing brothers.

Occasionally we find references to other

German companies such as Hoffmann, Carette and

Falk and the Lapierre firm from

France. Prices vary from some guilders to some tens of guilders. The children's

lanterns go with small oblong glass lantern slides, measuring 2-6 cm width. The

pictures on them are about fairy tales, caricatures, panoramas, sea views (often

four pictures side by side against a black background. In the latter half of the 19th century well into the 20th century,

the lantern’s domestic use was flooded by a new market: the toy lantern, bought

especially for children. In

the Netherlands toy lanterns were mainly bought from the German manufacturers

Ernst Plank and the Bing brothers.

Occasionally we find references to other

German companies such as Hoffmann, Carette and

Falk and the Lapierre firm from

France. Prices vary from some guilders to some tens of guilders. The children's

lanterns go with small oblong glass lantern slides, measuring 2-6 cm width. The

pictures on them are about fairy tales, caricatures, panoramas, sea views (often

four pictures side by side against a black background. The long small toy slides also predominantly came from Germany (Bing, Plank,

Falk, Carette, Roose, Ross, Jenisch). The larger 8,3 x 8,3 standard slides were

either obtained from Germany (Liesegang, Unger and Hoffmann) or England (Primus,

Butcher & Sons, Newton & Co, Hughes, York & Son, Bamforth and others).

The long small toy slides also predominantly came from Germany (Bing, Plank,

Falk, Carette, Roose, Ross, Jenisch). The larger 8,3 x 8,3 standard slides were

either obtained from Germany (Liesegang, Unger and Hoffmann) or England (Primus,

Butcher & Sons, Newton & Co, Hughes, York & Son, Bamforth and others).

The small movable slides again came from Germany, the large mechanical slides from England.  This also concerns photo positives on glass and especially the

chromatropes or colour changers: two discs of glass in a wooden frame that

produce beautiful kaleidoscopic fire work effects. This also concerns photo positives on glass and especially the

chromatropes or colour changers: two discs of glass in a wooden frame that

produce beautiful kaleidoscopic fire work effects.

In the seventies of the 19th century extensive manuals for the use of the magic lantern appear. A well known example is ‘De tooverlantaarn, de wijze van samenstelling en gebruik alsmede de kunst om een geest op te wekken door een spook’ (translated from 'The Magic Lantern. How to buy and how to use it; also How to raise a Ghost, by 'a mere Phantom'. London, Houlson and Wright, 1870). Later the firm C.A.P.I. published a row of comprehensive manuals and catalogues. |

|||

|

Domestic shows A favourite was a lantern show at children’s parties, mostly presented by a member of the family but it was also not uncommon to hire a lanternist for this occasion.  A

children’s magazine from 1844 describes such a show in the family circle: “Uncle

has brought a lantern. He also projects the pictures”. On show is a flying night owl,

the movement imitated by moving the image across the lens, followed by a

harlequin on a tight rope. Next the history of Pieter Spa who wanted to

participate in the coronation celebrations held in London ("he takes the wrong

steamship and ends up in France, a comical spectacle"), including some birds

that pull a man up into the sky. Besides that, there are scary images of tigers and

wolves. The repertoire includes many comic scenes such as the

life of Punch and A

children’s magazine from 1844 describes such a show in the family circle: “Uncle

has brought a lantern. He also projects the pictures”. On show is a flying night owl,

the movement imitated by moving the image across the lens, followed by a

harlequin on a tight rope. Next the history of Pieter Spa who wanted to

participate in the coronation celebrations held in London ("he takes the wrong

steamship and ends up in France, a comical spectacle"), including some birds

that pull a man up into the sky. Besides that, there are scary images of tigers and

wolves. The repertoire includes many comic scenes such as the

life of Punch and

some

moving slides. some

moving slides.The Dutch writer Jacob van Lennep later in his life remembers such a show and describes in 1857 a performance of the lanternist Laurens, who went round Amsterdam circa 1810 to project his wares for children's audiences: "At the start of the performance Laurens turned his lyre and the children were asked to dance. Then he pulled the tablecloth tight across the wall and placed his lantern opposite on a table. He lit the tallow candle in the lantern whilst all the other candles in the room were blown out. The show can begin: before a spellbound children’s audience the lanternist holds a kind of prologue about the lantern. The projections are accompanied by stories: biblical scenes; Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, Noah’s Ark, the parable of the Prodigal Son. Besides that there were slides of Punch and his children, soldiers, ducks swimming in the water and Sir Augustine. Laurens always ended his show with the story of the baker’s wife who has a fight with the devil and pulls his tail." |

|||

|

The annual fair The annual fair was an important event in the 19th century. It was a combination of information, entertainment, amazement and sensation.  All

sorts of artists and showmen presented a mixture of amusement, art, technology

and science. The street singer illustrates his songs by means of self painted

pictures, printed on 'smartlappen' (Dutch for 'tear-jerker'. A 'lap' is a piece

of cloth). Performers of all kinds of visual entertainment present their tricks:

de 'rarekiek' (by means of an enlarging objective the spectator saw

three-dimensional images), the camera obscura, the panorama, the diorama and

last but not least the magic lantern. In the silhouette theatre the magic

lantern is used to project a background. The magic lantern shows offer

information about for instance historical events, biblical scenes, news items

from home and abroad, views from faraway countries, as well as humorous slipping

slides or other moving pictures, visual puns and chromatropes. All

sorts of artists and showmen presented a mixture of amusement, art, technology

and science. The street singer illustrates his songs by means of self painted

pictures, printed on 'smartlappen' (Dutch for 'tear-jerker'. A 'lap' is a piece

of cloth). Performers of all kinds of visual entertainment present their tricks:

de 'rarekiek' (by means of an enlarging objective the spectator saw

three-dimensional images), the camera obscura, the panorama, the diorama and

last but not least the magic lantern. In the silhouette theatre the magic

lantern is used to project a background. The magic lantern shows offer

information about for instance historical events, biblical scenes, news items

from home and abroad, views from faraway countries, as well as humorous slipping

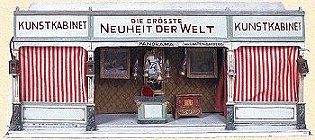

slides or other moving pictures, visual puns and chromatropes.This also takes place during the 1895 World Fair in Amsterdam. In the morning edition of 'Het Handelsblad' from August 19 we read: As from August 16 again some shows were presented on a stretched large piece of linen ... Now we have a brand new spectacle, very capable to give the audience a delightful pleasure. In the two small houses ... now daily the Giant Magic Lantern is introduced, as it is improved by the great Edison. Presented are the most beautiful views from our beloved country and also art treasures, images of old Amsterdam; also landscapes with the change from day to night, quite marvellous to look at ... maybe of great importance for many people because one can sit down and make a voyage to unknown parts of the world at the same time. ... |

|||

|

Education In the middle of the 19th century the magic lantern acquires a more important role in the education of the people. Some corporations arise which use the magic lantern to bring and hold the morality at a high level. Those who visit such a lantern show are faced with a choice of devout and virtuous series. Clergymen and priests who don't have the gift of the gab illustrate their sermons in church by slides. Many of the biblical stories are converted into pictures on glass slides. Because it becomes possible to produce series of slides of photographic images, a more realistic presentation comes within arm's reach. Between 1870 and 1910 a new kind of photographic slides are added: costumed models posed in scenes or locations illustrate narratives, songs and other texts. Typical subjects of this so called life model series included didactic temperance tales of alcoholism, unemployment and other social vices. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

'Hope On', series of life model slides made by Bamforth & Co. |

|

Life model series were also made to illustrate popular songs and also lengthy services of songs consisting of a narrative interspersed with hymns and delivered as a religious service. The two most prolific manufacturers were the firms of Bamforth & Co. and York & Son. They made use of actors (local actors or even members of the photographer's family) photographed in a rather primitive painted setting. Scenery and attributes were often used again and again in other stories. The photographs are published on glass in large quantities. The black and white images were often coloured by hand. Because of the increasing quality of the magic lantern it is used more and more for education, instructions and for lectures. This starts at the end of the 19th century and continues till the Second World War begins. Catalogues from these years mention hundreds of slide series about countless topics and for almost all school subjects.  A great deal of the lanternists that made their appearance in the Netherlands, came from abroad, from Belgium, Germany or France. Itinerant lanternists from Belgium were often called 'Luikerwalen' because of their birth place Luik-Walloon. A well-known Dutch lanternist was the owner of fairground attractions Freark Bakkerus. In summertime he travelled from fair to fair with his ‘Kunstkabinet’ (Art Cabinet) where he showed stereoscopic images among other things. In addition in the period 1890-1930 he travelled around in wintertime to present his magic lantern shows in pubs and other rooms.  Fortunately

one of Bakkerus' slide programs from 1908 has been saved. The show was opened to

bring The last news: The earthquake in the South of Italy and The dreadful

catastrophe in the mines of Ham and The railway accident in Contich in Belgium.

Besides the program mentions The Dogs

and Monks of St. Bernard, Two merry Monday holders ('laughs

guaranteed'), Bob the Fireman or Life of the Red Brigade, Living in the slums

of London ('wonderful'), Voyages to several parts of the World, The last

expedition to the North Pole, Unexpected encounter ('laughs guaranteed'),

Danger at Sea and The Revenge of the Monkey ('very comical'). Fortunately

one of Bakkerus' slide programs from 1908 has been saved. The show was opened to

bring The last news: The earthquake in the South of Italy and The dreadful

catastrophe in the mines of Ham and The railway accident in Contich in Belgium.

Besides the program mentions The Dogs

and Monks of St. Bernard, Two merry Monday holders ('laughs

guaranteed'), Bob the Fireman or Life of the Red Brigade, Living in the slums

of London ('wonderful'), Voyages to several parts of the World, The last

expedition to the North Pole, Unexpected encounter ('laughs guaranteed'),

Danger at Sea and The Revenge of the Monkey ('very comical').Bakkerus was accompanied during the lantern shows by his nephew Peter Bonnet who established the Magic Lantern Museum in Sloten (Friesland) in later days. The museum exists in these days under the name Stedhűs Sleat. It accommodates one of the most extensive collections of magic lanterns and lantern slides of the Netherlands. |

|||

|

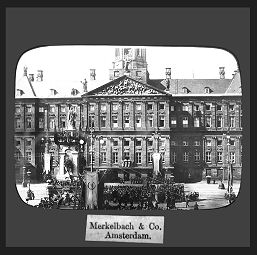

Sale and hiring out magic lanterns Between 1870 and 1950 in the Netherlands various photo shops that were specialised in the sales of lanterns and slides existed. Known examples are Zwartser in Haarlem, Van Senus in Rotterdam, Merkelbach in Amsterdam and C.A.P.I. in Nijmegen, den Haag, Groningen and Amsterdam. CAPI was a company formed by C.A.P. Ivens, the father of the well-known film director Joris Ivens. From 1900 to 1925 CAPI produced at least 40 catalogues dedicated to lantern apparatus, projection manuals and slide series.  They also published some projection manuals. The lists of series magic lantern slides

mention mainly samples of German and English make. However also series that are

made in the Netherlands are sold: Photographs of the Royal Family (the

coronation of Queen Wilhelmina in 1898), slides made by the glass painter Van

Staveren from Gouda (see sample below), photographs of the Dutch colony

Nederlands Indië, the well known blue cardboard boxes with City-series, de

series 'Ons Vaderland in Lichtbeeld' (Our Native Country in Slides) with

cityscapes, national costumes, and the common people from our own country ("also

very suitable for promotion of the Netherlands abroad") and not to forget Slides

for Mother and Midwife. They also published some projection manuals. The lists of series magic lantern slides

mention mainly samples of German and English make. However also series that are

made in the Netherlands are sold: Photographs of the Royal Family (the

coronation of Queen Wilhelmina in 1898), slides made by the glass painter Van

Staveren from Gouda (see sample below), photographs of the Dutch colony

Nederlands Indië, the well known blue cardboard boxes with City-series, de

series 'Ons Vaderland in Lichtbeeld' (Our Native Country in Slides) with

cityscapes, national costumes, and the common people from our own country ("also

very suitable for promotion of the Netherlands abroad") and not to forget Slides

for Mother and Midwife. A CAPI advertisement at the time states: “We take charge of projection needs

(limelight, electric light, etc.) across the whole of the Netherlands for

lectures and other presentations with slides, where the presenter brings his own

images. We provide a technical operator working the lantern as well as bringing

the projection screen. One knows a craftsman by his tools.... We also have

lanterns and manuals on hire to persons known to be familiar with the

technique." A CAPI advertisement at the time states: “We take charge of projection needs

(limelight, electric light, etc.) across the whole of the Netherlands for

lectures and other presentations with slides, where the presenter brings his own

images. We provide a technical operator working the lantern as well as bringing

the projection screen. One knows a craftsman by his tools.... We also have

lanterns and manuals on hire to persons known to be familiar with the

technique."Merkelbach in Amsterdam was another big Dutch firm dealing in lantern equipment. The 1911 catalogue nr 1 mentions: “To meet a growing demand we will put on shows using our dissolving views and the bioscope for parties, school events etc. We can also provide illustrations for lectures or other presentations. The cost for a Dissolving Views Show is 25 florins, whereas a Bioscope screening costs 60 florins.” In de eighties of the 19e century the firm of Merkelbach supplies a magic lantern to the Royal Family. The exchange of slides for the young prinses Wilhelmina was a regular occurrence. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

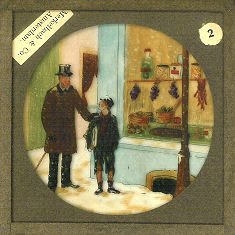

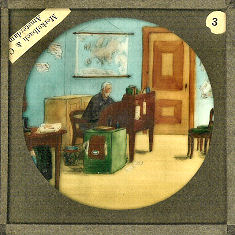

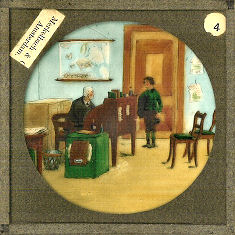

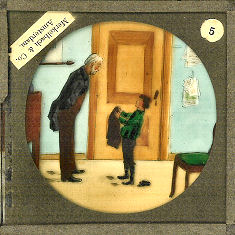

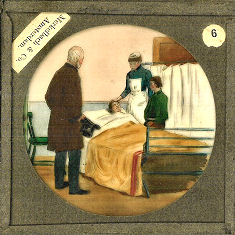

| Representative set of magic lantern slides about a poor paper boy, made by Merkelbach & Co. Amsterdam, 8.2 x 8.2 cm square. I interpret the story as follows: It's wintertime. The poor little paperboy meets a gentleman who turns out to be a doctor. Paperboy visits doctor's consulting hour and offers his jacket in exchange for help. His brother is serious ill. Doctor visits his brother, hopefully without accepting the boy's jacket. | ||

|

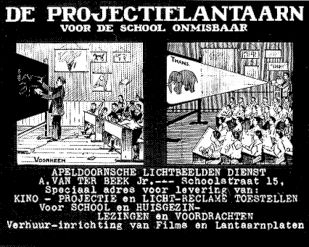

Lectures Between 1870 and 1940 many Dutch towns had their own hire centres, the so-called Slide Services. Good practice examples are: the Apeldoornsche Lichtbeeldendienst, the  Maatschappij tot Nut

van het Algemeen, the Lichtbeelden Vereniging, the Lichtbeelden Instituut, the

Centraal Projectie Instituut and the Lichtbeeldendienst D. van Kreveld in

Amsterdam. These organisations hired out apparatus as well as slide series,

besides offering appropriate readings. Maatschappij tot Nut

van het Algemeen, the Lichtbeelden Vereniging, the Lichtbeelden Instituut, the

Centraal Projectie Instituut and the Lichtbeeldendienst D. van Kreveld in

Amsterdam. These organisations hired out apparatus as well as slide series,

besides offering appropriate readings.The growth of the cinema from around 1900 led to the gradual disappearance of the magical and versatile lantern shows. The lantern’s special effect entertainment with illusion, movement, and showing strange phenomenon that could not be made clear was soon taken over by film. Yet, as in so many other 'lantern-countries', the slide presentations in the Netherlands persisted on a regular scale even beyond the Second World War. However the lantern was used more and more to educate and inform. The Magic Lantern became the Optical Lantern, a projection apparatus used for illustrating lectures. A letter from the 'Centraal Bureau voor Lantaarnplaten' from 1932 reports: "We are about to fulfil the role of 'Public Reading Room' in magic lantern slides for our entire country ... the use of our collection is frequently ..." The 1933 Anual Report says: "... We have at our disposal a collection of circa 50,000 lantern slides which can be lend out for education in all its forms and for social purposes ...".  Research from the local history group Heerenveen found numerous announcements and reviews

of lantern use in the Friesian province in the period 1893-1910.

Here we find a strong presence of the Salvation Army (Leger des Heils). They

were the only organisation in this period that persisted with their message

driven lantern meetings, yet included a good mix of moral and biblical stories

with profane (mostly comical) stories, photographic series, and moving effect

slides. The group Heerenveen also found a lot of announcements and commentaries

of other lantern shows in the province Friesland. Mostly they were referring

to Slide Lectures. Research from the local history group Heerenveen found numerous announcements and reviews

of lantern use in the Friesian province in the period 1893-1910.

Here we find a strong presence of the Salvation Army (Leger des Heils). They

were the only organisation in this period that persisted with their message

driven lantern meetings, yet included a good mix of moral and biblical stories

with profane (mostly comical) stories, photographic series, and moving effect

slides. The group Heerenveen also found a lot of announcements and commentaries

of other lantern shows in the province Friesland. Mostly they were referring

to Slide Lectures.

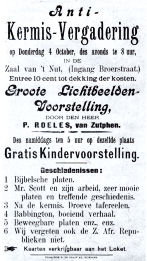

Organisations and individuals with a clear objective arranged meetings, using the slides as a way to attract audiences. Examples found in the Friesian newspapers from the period 1893-1910 are:

|

||

|

||

One unique example of the use of the magic lantern as a propaganda medium is shown

in the public debate that fuelled the Case Hogerhuis: an action in 1900 to

demand the release of three unjustly condemned brothers. The three got heavy

sentences (6, 11 and 12 year) for alleged burglary and attempted

manslaughter. Their conviction was set to make an example, their punishment

meant to discredit the socialist movement. In 1900 a series of protest meetings

were organised to free the brothers. They were announced as follows: “Grand

Public Meeting with Magic Lantern Slides to help the cause of the innocently

convicted brothers Hogerhuis”. Slides invigorated action to liberate the three

condemned. Nevertheless, it was in vain. The three were not freed. One unique example of the use of the magic lantern as a propaganda medium is shown

in the public debate that fuelled the Case Hogerhuis: an action in 1900 to

demand the release of three unjustly condemned brothers. The three got heavy

sentences (6, 11 and 12 year) for alleged burglary and attempted

manslaughter. Their conviction was set to make an example, their punishment

meant to discredit the socialist movement. In 1900 a series of protest meetings

were organised to free the brothers. They were announced as follows: “Grand

Public Meeting with Magic Lantern Slides to help the cause of the innocently

convicted brothers Hogerhuis”. Slides invigorated action to liberate the three

condemned. Nevertheless, it was in vain. The three were not freed. |

||

|

The magic lantern nowadays  One of the largest collections of the Netherlands is lodged in the Stedhűs Sleat museum in the town of Sloten (Friesland). Peter Bonnet's collection is shown there in a sublime contemporary presentation.

Other places in our country where magic lanterns and slides can be found are: the Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam, a lot of toy musea, Museum Boerhaave in Leiden and the Prentenkabinet of the University of Leiden. The Word Wide Web accommodates quite a number of fascinating magic lantern sites. In the Netherlands is magic lantern site 'de Luikerwaal' - www.luikerwaal.com - an absolute must for everybody who wants to know more about the magic lantern. Some seven lanternists and collectors in the Netherlands are members of the English Magic Lantern Society. A number of them present magic lantern shows regularly. The author of this article is one of them. |

||

| |

©1997-2021 'de Luikerwaal' All rights reserved. Last update: 27-05-2021. |